And thus the snowdrop, like the bow

That spans the cloudy sky,

Became a symbol, whence, we know

That brighter days are nigh.– Scottish poet George Wilson, 19th century

As landscapes shed winter’s heavy cloak of gloom and grey, the winter-blooming snowdrops begin to herald spring. These fair yet hardy maidens of February can even emerge through snow earning them the French name Perce-Neige, which means to “pierce snow.”

This daintier member of the Amaryllis family (Amaryllidaceae) was first described as Viola albus, or leucoion (white violet), around 350 BC by Theophrastus, known as the Father of Botany and author of the ancient Greek text Historia Plantarum (Enquiry into Plants). There is debate over whether snowdrops were also referenced in Homer’s Odyssey in the form of an herb called moly, which Hermes gives Odysseus to protect him from Circe. Homer’s description of the possible snowdrop:

“The root was black, while the flower was as white as milk; the gods call it Moly, dangerous for a mortal man to pluck from the soil, but not for the deathless gods. All lies within their power.”

In 1753, Carl Linnaeus named the genus of snowdrops Galanthus, derived from the Greek words gala (milk) and anthos (flower). He also named the common snowdrop Galanthus nivalis, with nivalis meaning “of the snow.”

John Gerard, a noted herbalist and botanist during the Elizabethan Era, referred to the snowdrop, like Theophrastus, as a white violet and noted their lack of medicinal properties (Schramm 2016). However, in the 1950s, it was discovered that people in the Ural Mountains of Russia used mashed snowdrops as a pain reliever (Rathbun 2018). Phytochemists later found that Galanthus produces several pharmacologically significant alkaloids, including galantamine, which improves cerebral function and was subsequently used in the development of possible Alzheimer's disease treatments (RHS).

It is believed that in the 15th-century, Italian monks introduced snowdrops to British monastery gardens, where they spread throughout Britain, possibly aided by local flooding (Lee 1999). Following the Crimean War, soldiers are said to have brought snowdrops back to the UK, contributing to their renewed popularity.

Having explored the historical significance of snowdrops in Greece, Russia, Italy, and the UK, let's briefly journey to Germany. The iconic drooping flower head, which helps protect the pollen from winter moisture, is reflected in the German word for snowdrops, "schneetropfen." Interestingly, "schneetropfen" is also used to describe drooping earrings, akin to the earring depicted in Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring. Furthermore, the term "drop" in the common name "snowdrop" harks back to an archaic word for an earring.

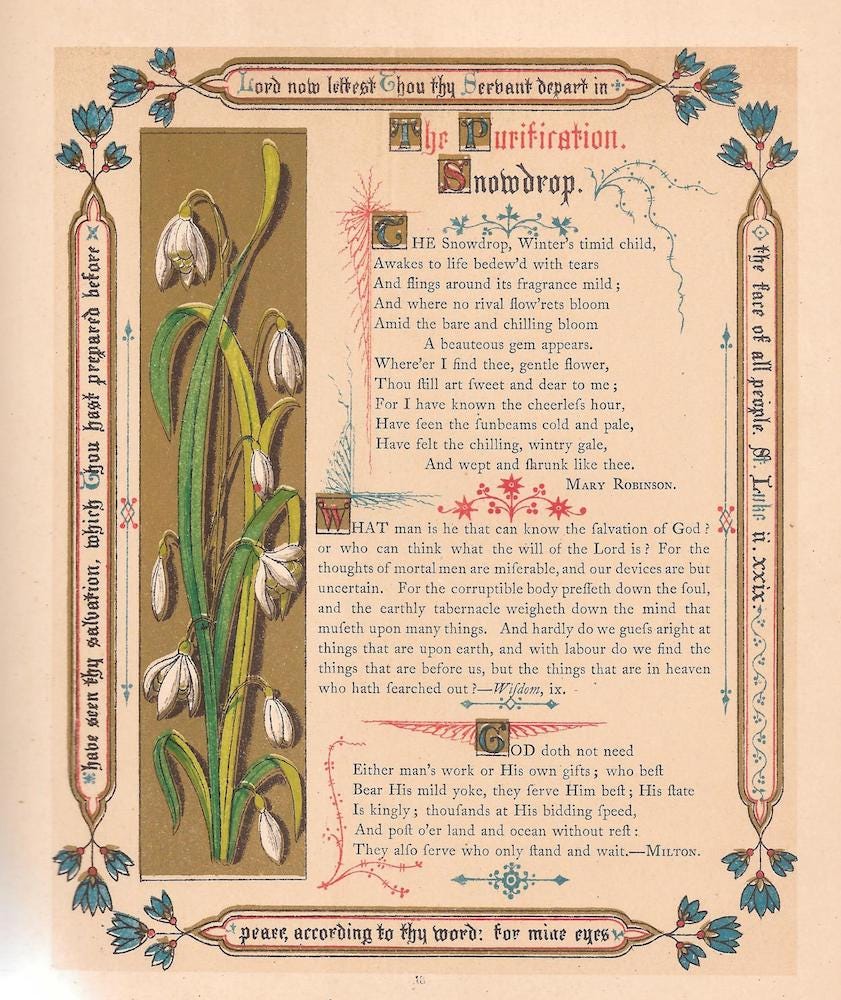

The snowdrop’s historical symbolism of hope and purity was further emphasized by village maidens who adorned themselves with garlands of snowdrops and scattered them before the candlelit image of Virgin Mary for the Christian feast of Candlemas on the 2nd of February, earning them the old common name Candlemas bells (Fisher, 2013). I believe this tradition of wearing snowdrop crowns is depicted in Frederick Sandys’ painting Apple Blossom, as well as in the delicate snowdrops and crocus adorning Proserpina’s head in his work Gentle Spring (1865).

“The Snowdrop, in purest white array, First rears her head on Candlemas day.”

In the Victorian language of flowers, these delicate blooms continued to symbolize purity and hope. However, their significance evolved as Victorians started planting them in graveyards, leading to the ominous moniker "death flower." In early 19th-century folklore, it was considered unlucky to bring them into the house.

“So much like a corpse in a shroud that in some counties the people will not have it in the house, lest they bring in death.”

—Margaret Baker, ‘Encyclopedia of Superstitions, Folklore and the Occult of the World’ (1903)

Interestingly, cottagers also lined the path to their privies and were guided by the glow of the snowdrops in the moonlight (Lee 1999).

In modern history, Heyrick Greatorex is recognized as the first snowdrop breeder, pioneering the cultivation of various cultivars in his garden, which he aptly named the Snowdrop Acre (Rushton 2019). Interestingly, many of his creations were named after characters from Shakespeare's plays, despite snowdrops never appearing in the works of Shakespeare himself.

You can read more about Greatorex’s Shakespearan double snowdrops here:

Fear no more, thou timid Flower!

Fear no more the winter’s might,

The whelming thaw, the ponderous shower,

The silence of the freezing night.– Samuel Taylor Coleridge, The Snow Drop

Across history and around the world, this tiny flower has symbolized hope. As the story goes, after Adam and Eve were banished from the Garden of Eden, they faced seemingly endless winter. As Eve despaired, an angel transformed the snowflakes around her into a carpet of snowdrops, signifying the first sign of spring.

Also, for any readers in the dead of winter, daydreaming of immersing yourself in springtime blooms in the garden, I recommend watching the videos of alpine gardener, Ian Young:

“Above the garden beds, watched well by lady’s eye

Snowdrops with milky heads peep to the softening sky,”

– Miss Taylor

Through the Amazon Affiliate Program, any eligible purchases you make through Amazon links on this post will help me earn a commission at no extra cost to you. Your support is greatly appreciated in furthering the growth of The Pleasaunce! 𓇗

Update: Since first writing this blog post, I have inevitably become an amateur galanthophile.

References

Cambridge University Botanic Garden. Snowdrops.

Fisher, Celia. The Medieval Flower Book. 2013. p. 111

Lee, M. R. The Snowdrop (Galanthus nivalis): From Odysseus to Alzheimer. Proceedings of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, vol. 29, 1999, pp. 349-352.

Tyas, R. The Language of Flowers, or, Floral Emblems of Thoughts, Feelings and Sentiments, 1875.

Schramm, B. Snowdrops: Science, Myths, and Folklore. New York Folklore, vol. 42, no. 3-4, 2016, pp. 46-47.

Royal Horticultural Society. “The Snowdrop: Winter’s Timid Child”, 2018.

Rushton, S. “Heyrick Greatorex: The Founding Father Of Snowdrop Breeders,” 2019.

Ward, B. J. A Contemplation Upon Flowers: Garden Plants in Myth and Literature, 1999.

Further Reading

Snowdrop Gardens & Festivals in the UK

Making lists is one of my favorite activities—there’s something about the blend of hope for the future and commitment to oneself. Plant lists, in particular, soothe the longing for a garden of my own. As I sit in my apartment writing this, I find myself especially drawn to snowdrops, the delicate heralds o…